Are U.S. universities so good because of our organizational practices, or are we just really rich?

This is a reflection I wrote after a trip to Kazakhstan in May 2024. It narrates our travels and how it relates to my thoughts on higher education organizational behavior. I spend some time thinking about one of the theories I can’t seem to quit, isomorphism.

Subtitle: Thoughts on colleges and universities after encountering Kazakhstan’s higher education system.

TLDR (keep some Large Language Model related carbon out of the atmosphere and just skim this section if your in a hurry)

Full disclosure: I’m entering the weekend before finals so I doubt I’ll have time for much original thinking for the next 2 weeks.

I am resharing (with light editing) a reflection I wrote for a HALE International Higher Education course which included a trip to Kazakhstan in May 2024. It’s a narrative of what we did while in the country and how it related to some of my thoughts on higher education organizational behavior. I spend some time thinking about one of the theories I can’t seem to quit, isomorphism. Happy December!

Kazakhstan Postsecondary Education and Cultural Legacy vs. Global Aspirations

My current conclusions about the meaning I should draw from my recent academic program trip to Kazakhstan was planted in a tiny museum. While visiting Kazakh National Women’s Teacher Training University (QYZPU) we were ushered into a room that doubled as an exhibition of the institution’s history, and Kazakh history from a feminine perspective. Distributed among the artifacts meant to represent both the influence of Soviet education policy and Kazakh indigenous history I saw a public institution trying to reconcile its complicated colonial and idealized indigenous influences.

Based off my observations from that day and the rest of the trip, I believe a similar push-and-pull of embracing Kazakh cultural distinctive versus leaning into global definitions of institutional quality is influencing the behavior of Kazakh postsecondary education institutions. When contextualizing this observation with my experiences and perspectives on U.S. postsecondary education organizations (POs) I’m led to ask the question “did U.S. distinctive elements of postsecondary education like faculty independence, shared governance, wholistic student development, and institutional autonomy foster our institutional dynamism OR are we just really rich?”

In this post I argue that global isomorphic dynamics challenge Kazakh postsecondary education institutions to consider whether they will lean into their cultural legacies and historical roots, or strive to adopt practices and policies that will enhance their global prominence. To build my case I will define an organizational theory called isomorphism, then briefly highlight observations I made during site visits conducted during a trip to Almaty and Astana in May 2024 as a part of a Higher Adult and Lifelong Education (HALE) comparative higher education course. I will blend observations with references to course readings to build my case. After sharing my observations I’ll provide some concluding thoughts to tie the whole experience together.

Isomorphism and Higher Education Institutional Behavior

Postsecondary education systems are subject to global isomorphic pressures. Isomorphism is a concept that argues organizations that exist within a common organizational field (such as colleges or universities) over time are incentivized or coerced into adopting similar organizational structures and behaviors (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). This dynamic exists because organizations must respond to challenges or opportunities within the context of their common organizational field. In the case of postsecondary education organizations are constrained or unbound through a complex set of interactions between the globalized economic, legal, professional, and cultural frameworks the organizations operate within (Zapp & Ramirez, 2019). I believe the observations I made in Kazakhstan fit this model of organizational theory.

SDU Global University

Located in an Almaty suburb SDU Global University is a private institution with an ambitious growth plan. As the first institution we visited, there were several themes we encountered that were reinforced on later visits. SDU was building. Officials there were quick to highlight their new facilities and ambitions for expansion. They shared information with us about their QS and Times Higher Education (THE) rankings. During our round of discussion with administrators they highlighted their strengths as a private institution that didn’t face the same challenges as legacy/public Kazakh postsecondary institutions.

(A screenshot of SDU promoting its Times Higher Education ranking.)

Most students enrolled at the institution attended on a state grant. This presented challenges because the amount of tuition that these students could be charged was capped by the grant ceiling. When discussing the curriculum preferences of students administrators reported that English was the predominate language of instruction.

(During our visit to SDU students were completing their final exams. This captured an exam completion tradition.)

In listening to the particularities that SDU officials shared with us a few themes emerged 1) there is high demand for access to postsecondary education, 2) definitions and distinctives of quality were important for making globally ambitious claims, 3) postsecondary institutions were defining themselves in relation to current government policy and the legacy of Soviet civic institutions. Each of theme is an avenue to think about the institutional factors of cultural legacy and global aspiration. These themes are reflected in our class readings.

Saule Anafinova (2020) examined how rankings applied to higher education policy in Kazakhstan induced isomorphic pressure on postsecondary institutions. Their study looked at special status “National Universities” (two of which we visited). These institutions received funding incentives to improve their standing with Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) rankings and Kazakhstan Education Ministry rankings. Anafinova finds that the Education Ministry ranking criteria began to mirror QS criteria. Institutions are shown to create strategic plans to increasing their rankings against the stated criteria and some adjusted their institutional mission statements. However, after an initial burst of rankings improvement the standing of the National universities has remained constant. They argue Isomorphic pressure has led institutions to adopt common language and strategic planning, but long term increases in global standing remain elusive.

While not a National University designee, SDU adopted QS criteria to signal quality and improve their global standing. I believe staff comments about the “bureaucratic” challenges public institutions faced (like the National Universities) was an effort to signal that SDU’s nimbleness presented a more likely avenue for achieving global recognition. While prominent Kazakhstan alumni are celebrated in photos and murals SDU fully embraces a brand as an institution with a global footprint.

Kazakh National Woman’s Teaching Training University (QYZPU)

QYZPU is a public National University with a teacher training focused academic program. The institution is also a women serving institution. They were founded by the Soviet Union during WWII to address a need for primary school teachers. During our visit we met with faculty and PhD students enrolled at the institution. I was impressed by QYZPU’s institutional story and focused mission.

(Images taken while walking the halls of QYZPU)

Even during major renovations the QYZPU campus walls were plastered with images and artifacts of the institution’s history, and prominently celebrated its alumnae. Contrary to SDU, the curriculum at QYZPU was taught primarily in Kazakh and some Russian. Educational Ministry policy was more prominently discussed at QYZPU than it had been at SDU. The composition and program quotas for the state grants given to enrolled students was discussed as having an important role in institutional academic resource allocation. Government initiatives to increase interest in teacher training programs were also cited as impacting institutional priorities. When discussing government incentives for institutions like QYZPU achieving international prominence the phrase “bringing global quality vs. being coopted by global quality” was utilized. It was jarring to encounter the depth of discussion of national dynamics presented after our preceding site visit was so globally focused. The differences between SDU and QYZPU illustrates dynamics highlighted in literature we read associated with the transformation of Kazakhstan’s higher education after its transition out of the Soviet Union.

Anna Smolentseval, Jeroen Huisman, and Isak Froumin (2018) wrote a book chapter reflecting on the influence and future of postsecondary education in post-Soviet countries. They highlight an important factor that has influenced post-Soviet institutional reform has been the adoption of Bologna process standards, and international aid that flooded provided by western governments in an effort to shore up diplomatic influence. As a result, institutional reforms have adopted a predominately U.S./Western European framework in terms of stated institutional goals (such as research quality, labor market considerations). Appeals to international third-party accreditation from Europe and global ranking systems has reinforced this movement. While “western” language around education organization values have been adopted, there is still an element of Soviet-style central planning present within the governments policy implementation strategy. As administrators at QYZPU and SDU highlighted, while their institutions are encouraged to bring in international students and collaborate internationally, the government maintains central planning like influence over the direction of postsecondary education institutions through the state grant funding that opens a means for the majority of students to enroll in postsecondary education.

The observations of QYZPU administrators illustrates the push and pull between honoring cultural and historical distinctives while attempting to adopt what are perceived to be global practices. Literature we reviewed also highlights this push and pull doesn’t happen only at the organizational level. Aliya Kuzhabekova and Ainur Almukhambetova (2017) find that female leaders felt obligated to live up to standards imposed by traditional Kazakh culture, Soviet practices, and neo-liberal priorities. Study participants found it difficult to balance all three types of dynamics and found they appeared in different organizational or social contexts in different ways. To cope, female leaders engaged in code-switching with each leaders personal values and organizational role informing which codes took precedence and priority. I believe postsecondary institutions engaged in similar codeswitching. Each institution framed their choices and priorities differently, but each was contending with their organizational history and the priorities imposed by global postsecondary education forces.

Al-Farabi National University (KazNU)

We visited the International Relations program at Al-Farabi National University. KazNU is a public institution with national prominence due to its distinguished alumni and length of existence. Similar to QYZPU, KazNU was established by the Soviet Union. Its International Relations program in particular is important because it has been the primary educational pipeline for Kazakhstan’s diplomatic corps.

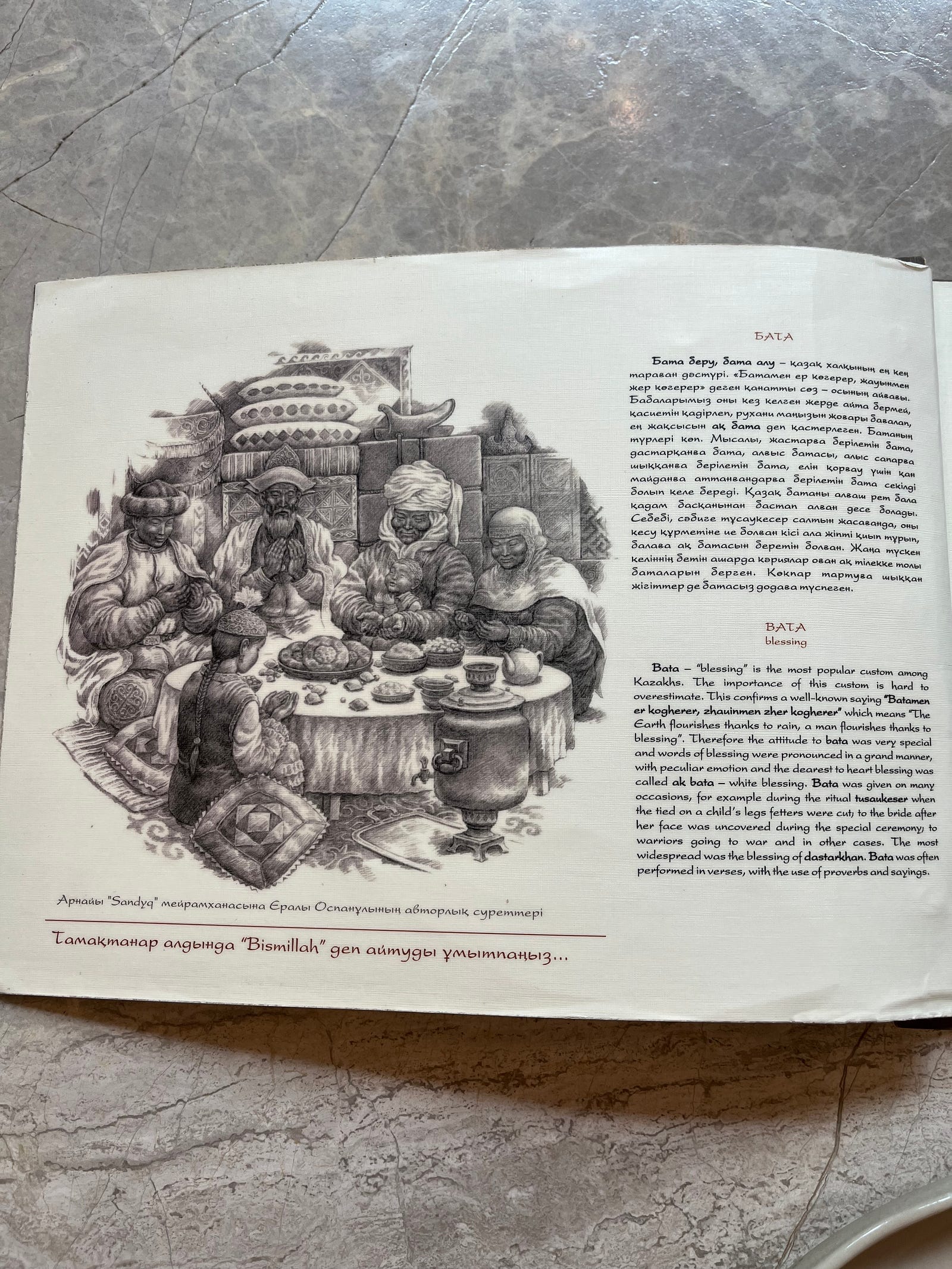

The recently renovated facility that housed the International Relations program at KazNU featured many prominent photos of alumni or institution representatives meeting with foreign leaders. The academic program was based on the Moscow diplomatic college program. The belt and road initiative and whether or not it influences students decision to study Chinese or English was discussed. There were difficulties with starting Chinese language based programs because of a lack of faculty and curricular resources. We also discussed Kazakhstan’s cultural legacy and a faculty member theorized that a distinctive of Kazakh statecraft is its malleability/adaptability. This was attributed to the nomadic nature of Kazakh indigenous history. Kazakh people have always been multilingual and preferred languages have shifted like the trade winds.

(An illustration of Kazakh hospitality rituals.)

During our visit we also discussed postsecondary enrollment and national k-12 policy. Specifically we discussed challenges with educational reform and the formation of a specialized set of schools called Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools (NISs). The framing was that NISs were meant to accelerate reform adoption at public schools. NIS schools are highly selective, with increased instructional funding provided through a special government appropriation. The students who attend them are put on a fast track for postsecondary enrollment either nationally or internationally. Using NIS was meant to circumvent resistance to adopting post-Soviet curricular approaches fueled by institutional habit and political corruption. This reform strategy provided another window into viewing the push and pull between cultural legacies and a globalized viewpoint.

Elise Ahn and colleagues (2018) overview of the Kazakhstan higher education system emphasizes that the government sees postsecondary education development as an important part of statecraft. This argument is bolstered by our discussion with KazNU faculty. The primary language of instruction was framed as signaling a student’s educational priorities whether focused on opportunities within Kazakhstan, Russia, China, or the U.S./Europe. The belt and road initiative is discussed in research by Jack Lee and colleagues (2021) who argue that engagement with the belt and road initiative by Kazakhstan postsecondary institutions exhibits a utilitarian approach which resists intended Chinese framings of the initiative as a global community project. They also found that Kazakh postsecondary institution leaders framed the Kazakhstan government as being the primary driver of institutional reform. This is an example of cultural legacy causing friction with the adoption of globalized practices.

Narxoz University (NxU)

Narxoz University is a private non-profit institution created when a holding company bought a Soviet established economics institute. The holding company manages the appointment of the institutions board of directors and conducts “corporate governance” audits. Stakeholders can purchase shares of the holding company to gain some influence over board appointments. The institution hews close to its economics roots with business/finance and legal degrees being popular programs.

Like all the institutions we visited, Narxoz was experiencing a building and renovation boom. We met with members of the administration and faculty. NxU, like SDU emphasized its QS and THE rankings. There were lots of markers of corporate sponsorship on walls and near entrances. The institution talked about its initiatives to support and expand opportunities for international student outreach and support.

A video promoting the corporate sponsorships and career opportunities for Narxoz students.

Our time with NxU faculty revealed elements of faculty life in Kazakhstan. The focus of the faculty role is maximizing teaching. Tenure is not an organizational priority. Faculty worked on 1–5-year contracts and their teaching performance was monitored closely. The faculty also talked about navigating constant change because of shifts in government priorities. They talked about how social demand for postsecondary education access has pushed the government to significantly expanded state grant issuances. Many of the new students who would not have previously scored high enough to achieve a grant were not prepared to succeed academically.

Faculty at NxU reiterate the observation from KazNU that the NIS circumvention strategy was an effective means of reforming the educational system. While not perfect, the faculty member felt the results were systemically positive because it forced lethargic and complacent public schools to adapt. In this reform effort I see efforts to reckon with cultural heritage while embracing elements of international frameworks for curricular formation and educational administration.

Aida Sagintayeva and Kairat Kurakbayev conducted research (2015) looking at efforts by Kazakh postsecondary education institutions to adopt administrative practices that would indicate institutional autonomy like western European or U.S. postsecondary education institutions. They found that a combination of inherited Soviet administrative practices, government practices, and institutional leadership expectations hindered the ability of institutions to embrace autonomy. They conclude by arguing that policy makers need to be consistent in promoting autonomy with an understanding there will be unintended consequences, and university leadership need to let go of their acceptance of centralized control. This study aligned with our discussion with NxU faculty. In their framing government funding is too important to risk losing by bucking education ministry norms, and policy shifts too quickly to allow for the institution to set up autonomous priorities and structures.

National Academy of Education

The national academy is an apparatus of the Education Ministry that supports the implementation of education policy and acts as a point of contact and advocacy on behalf of education institutions. The academy focuses on k-12 policy and curriculum. Our visit focused primarily on pathways from secondary to postsecondary education.

During our visit with officials we talked about the NIS program. Many of the viewpoints from NxU and KazNU faculty were repeated to us. Much of the academies work on curricular formation was attempting to update the curriculum to take reflect a learning approach from European and U.S. contexts. When asked about the distinctives of the Kazakh education system compared to the rest of the globe academy officials talked about participation rates, the high percentage of students who achieve proficient standards, and the balancing of formative vs. summative methods of learning assessment. The Soviet style included close daily scrutiny of students and this proclivity has been inherited by the current generation of Kazakh parents.

During our visit a lot of the academy staff made it clear to us they were interested in finding avenues for research collaboration. They were very interested in whether we had recommendations for getting their work featured in Scopus. I interpret these questions as an example of government incentives pushing educators to adopt global standards of quality and legitimacy.

Here’s a link to an instagram video promoting our visit to the academy.

Nazarbayev University (NU)

Nazarbayev University (NU) is intended to be the best postsecondary education institution in the country (when defined by common global standards of research output and student metrics). Nazarbayev faculty are privileged with work expectation structures that incentivize the pursuit of knowledge production. NU receives an additional funding allocation that ensures faculty pay is globally competitive (not just nationally or regionally), that there is funding for research endeavors. Modeled on a “flagship” or “multiversity” institutional model NU is meant to accelerate the perception of Kazakhstan as a bastion of quality postsecondary education and global knowledge production/knowledge economy participation. It also replicates some of the unintended consequences of the Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools — it is insular, and privileges “western” forms of organization and cultural expression over legacy organizational forms or cultural expression.

(Pictures of Nazarbayev University. Note the corporate sponsorship and startup banners. The juxtaposition of banners celebrating corporate sponsorships and third party rankings with the astroturf sitting areas struck me as apt.)

We did not get as much extended engagement with administrators and faculty like we did at our previous site visits. Much of what I concluded about NU was through observation instead of dialogue. One article we read by Munyaradzi Hwami (2024) about the geopolitics of knowledge informed many of my observations. The article argued that in pushing for internationalization at institutions like NU, the incentives provided pushed a worldview and that presumed the superiority of western European or U.S. organizational practices. Their study interviewed administrators with extensive internationalization experience or were graduate students at international institutions. They found an overwhelming preference for western epistemological frameworks. Study participants felt pressure to seek credentials at western institutions because of the perceived superior competence such a degree would impart. English was the most desired language for publication. Hwami concluded that “participants in this study seem to be buying into the notion of an advanced West economically, politically and socially which for them is the model or status Kazakhstan should learn from and emulate” (p. 14).

Many of the markers observed at other institutions were observed at NU. There was extensive renovation. Artifacts of corporate sponsorship were highly visible. Institutional rankings were proudly displayed. Given my observations of the challenge of balancing cultural legacy with global aspirations I’m inclined to believe that the lack of artifacts is a reflection of an aspirational bias towards global definitions of quality and prestige.

Concluding Thoughts

During our visit to KazNU a faculty member remarked that “Young people want diplomas and the government wants to expand visibility in education on the world stage.” Efforts to achieve both demands pushes postsecondary education institutions to balance their cultural legacy against the organizational practices favored by a globalized higher education ecosystem.

The private institutions and Nazarbayev University displayed the adoption of organizational practices most aligned with the global ecosystem, while the public institutions with the oldest histories highlighted their historical roots and influence. I’m left with the question of whether the globalized ecosystem practices that include hallmarks of the U.S. postsecondary system like institutional autonomy, academic freedom, and shared governance are what is required for a flourishing ecosystem, or whether their prominence is tied to the massive financial resources U.S. and western European institutions have accrued. I’m inclined to believe that the western hallmarks I’ve mentioned are good practices, but these western hallmarks require a stable policy ecosystem. To presume their superiority is to globalize the blind-spots our organizational practices engender. The private Kazakh institutions and NU provide a useful test case for what less resourced institutions must do to compete with rich institutions. The result is frequent organizational change, a relinquishing of organizational vision to third-party rankers, and infusions of capital from corporate interests. It’s not clear to me that in the compromises necessary to operate in a global ecosystem that these institutions will eventually be able to pivot to adopt governance and academic structures that reflect the U.S. governance and research models.

My time in Kazakhstan left me humbled. The capability of administrators and faculty to navigate the constant change and competitive demands on the limited budgets they have was impressive. It also inspires me to look for avenues to celebrate alternative epistemological and culturally rooted academic endeavors. The funding and brain-space for such projects may be limited by the current Kazakh postsecondary ecosystem, but efforts to carve out an alternative set of practices and research agenda should be celebrated and elevated when identified.

References

Ahn, E. S., Dixon, J., & Chekmareva, L. (2018). Looking at Kazakhstan’s Higher Education Landscape: From Transition to Transformation Between 1920 and 2015. In J. Huisman, A. Smolentseva, & I. Froumin (Eds.), 25 Years of Transformations of Higher Education Systems in Post-Soviet Countries (pp. 199–227). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52980-6_8

Anafinova, S. (2020). The role of rankings in higher education policy: Coercive and normative isomorphism in Kazakhstani higher education. International Journal of Educational Development, 78, 102246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2020.102246

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. JSTOR Journals.

Hwami, M. (2024). A geopolitics of knowledge analysis of higher education internationalisation in Kazakhstan. British Educational Research Journal, 50(2), 676–693. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3949

Kuzhabekova, A., & Almukhambetova, A. (2017). Female academic leadership in the post-Soviet context. European Educational Research Journal, 16(2–3), 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904116682040

Lee, J. T., Lo, W. Y. W., & Abdrasheva, D. (2021). Institutional logic meets global imagining: Kazakhstan’s engagement with China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Higher Education, 82(2), 237–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00634-y

Sagintayeva, A., & Kurakbayev, K. (2015). Understanding the transition of public universities to institutional autonomy in Kazakhstan. European Journal of Higher Education, 5(2), 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2014.967794

Smolentseva, A., Huisman, J., & Froumin, I. (2018). Transformation of Higher Education Institutional Landscape in Post-Soviet Countries: From Soviet Model to Where? In J. Huisman, A. Smolentseva, & I. Froumin (Eds.), 25 Years of Transformations of Higher Education Systems in Post-Soviet Countries (pp. 1–43). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52980-6_1

Zapp, M., & Ramirez, F. O. (2019). Beyond internationalisation and isomorphism — the construction of a global higher education regime. Comparative Education, 55(4), 473–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2019.1638103